Our Blog - Greece 2024 - Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae

After a bit of driving around the mountain tops, we arrived at the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae. Quite a long name for a single temple, but there are reasons for the name. There are multiple temples to Apollo, so the "at Bassae" makes sure that we know it is this one. The name of the site means “wooded gorges”. The area belongs to Mount Kotilio, which in turn is part of the mountainous mass of the mythical Lycaeon Mount of Arcadia with its many ancient cults. The "Epicurius" part of the name means "Helper", and this temple was constructed in the 5th century BC to give thanks to Apollo for their deliverance from the plague of 429–427 BC.

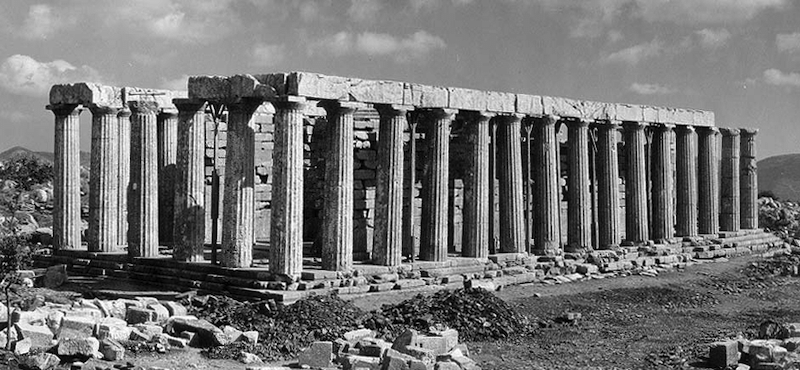

One website called it the "least known and least accessible" of all Greek temples, which I can understand, having driven on the roads to get to it. It was built on a natural rock plateau oriented North-South, which makes it also different from the usual East-West oriented temples. Most of it is built from local layered, gray limestone but some marble was used in the sculptural decoration. It is also longer than most classical temples of the time ... it has 15 columns on the long sides, compared to 13 in most temples. There are 6 columns across the short ends.

This is believed to be the first building that uses a Corinthian capital, but it also one of the few that uses all 3: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian columns. The exterior columns all have Doric columns (the very bland ones), then the inner row have Ionic capitals (the ones with circles). The Corinthian columns are at the very center. Around the top of these columns were 2 difference friezes: the exterior of the temple had a Doric frieze (similar to previous temples we have seen), which has the 3 up-and-down columns. One part of the inner frieze, which sat on top of the Ionic and Corinthian columns, depicted the return of Apollo to Olympus from the Hyperborean countries, and the abduction of the daughters of the Messinian king Leucippus by the Dioscuri. There are also 23 blocks of the frieze showing the battle between the Greeks and Amazons and the Lapiths and Centaurs. These 23 blocks are on display at the British Museum (room 16) and you can take a virtual tour to see the fragments of the frieze on the museum website.

I'll start with a few pictures that are not mine. These come from various places, like Wikipedia and the McGill University archives. The reason that I start with these is that I can't get you a picture with the whole temple now ... since 1987, the entire structure has been covered with a large tent. It was put in place to protect the temple from the deterioration of the limestone, as well as protecting workers while they are doing a bunch of conservation work. I'll talk about this a little as we go through the other pictures. The first 2 are before much of any conservation work, while the 3rd shows a bit of scaffolding on the interior parts.

.jpg)

So now we get to my pictures, which are much closer but are a bit more difficult to get a good image of the entire temple in your mind (hence the 3 earlier pictures). I have various pictures from different vantage points showing the exterior columns with Doric capitals and parts of the Doric frieze around the top. You can get a peek at the base of the temple and what the columns are sitting on, and then you can compare them to later pictures for the restoration work. Then you can see the walls that form the interior of the temple.

Close-up of the "boring" Doric capitals, just above the structural brace.

In the interior of the temple building, you can peek and see what I assume is the base of an altar in the middle (with the metal around it).

Back at the front corner, trying to get a view of size (with Tom next to it), the base with several levels of stone blocks, the columns across the short-side and the long-side.

Now I've moved to the other end of the temple, which is the "reconstructed" side. Here you can see that the base is not crumbling, and the columns and frieze no longer have the structural braces. The stone on the base are not just all new concrete, but if you check out the 2nd picture, you can see how they have inlaid "new" stone or concrete with the existing "old" stone from when the temple was built. But in this way, they can reinforce the base and make it flat. You can see the same sort of additions in the close-up of the frieze, although it does look like the columns are pretty much all original, which is amazing if you think about how old these things really are.

They have several videos (some on YouTube) that show the restoration work. Here you can see the 3 columns on the right-hand side ... these have been removed from the temple base while the work is in progress on the part of the base that they sat on. When the base has been fixed, they will be raised back up (with a special crane, it is pretty impressive in the videos) and then lowered back onto the platform.

Now I mentioned the flat base after the reconstruction .... these last 2 pictures hopefully will show why this is critical. The closer columns are on the restoration side and the far columns haven't been worked on (other than stabilizing them). Look how far they tilt outwards from the bottom to the top (compared to the straight up-and-down-ones closer in the picture). It seems like the entire temple is tipping over! That whole section of columns have braces around the top and a metal framework to keep it from tipping (I would imagine). So the restoration work takes each column, wraps it in supports, then lifts it out of the way and sits it on the side. The base stones are then "fixed" to get them stable and flat. Once they are returned to the structurally-improved base, they are straight and no longer need the support braces (which is why the ones on this side don't have the braces at the top).

Outside are lots of additional stone pieces, like this part of the exterior Doric frieze.

I guess we will have to now make another trip to the British Museum to look again at Room 16, since now, we can put them in context with the actual temple.